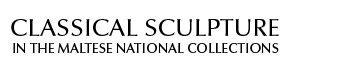

Portrait head of a bald man

Category

HeadsAbout This Artefact

I.D. no: 35691

Dimensions: H. 24 cm; W. 19 cm

Material: Coarse-grain white marble

Provenance: Unknown

Current location: National Museum of Archaeology

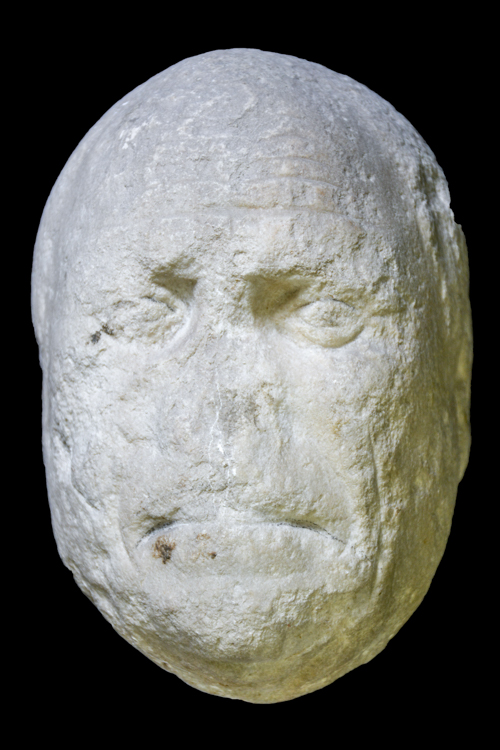

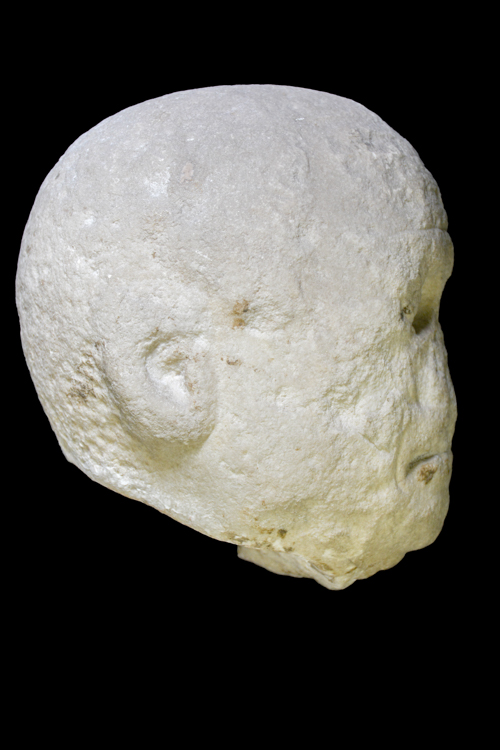

Condition: Only the head survives, and in a very bad state of preservation. Apart from the missing nose, and shattered right eye and eyebrow, lips and ears, the whole surface of the marble has been subjected to intensive battering and corrosion from the natural elements.

Description: The shape of the head is almost spherical, were it not for the slightly elliptical face, and its somewhat inflated lower half. The barely distinguishable eyes must have been small, almond-shaped and close to each other. The ears and the wide, slightly opened mouth are also hardly distinguishable. Two deep furrows separate the mouth from the cheeks; narrower, shallower, but sharper ones are visible beneath the heavy chin and on the forehead. The head was not completely bald since traces of a low hair cover are still visible. The portrait represents a man of very advanced age, indicated by the double chin and marked wrinkles.

Discussion: This badly preserved head must have belonged to that abundant series of Roman portraits of extreme realism, mostly assignable to the late Republican period (first three-quarters of the 1st century BC) and generally associated with the patrician ius imaginum,[1] of which both Polybius (Historiae VI, 53, 1-54, 3) and Pliny the Elder (Nat. Hist. xxxv, 6-8) give testimony, but the origins of which are to be sought in different traditions, such as Hellenistic Greek, Etruscan, native Italian, and even Egyptian ones.[2]

Though in its original state this head was inspired by the same spirit as that which motivated a series of excellent heads, such as the two from Ostia,[3] a few in New York,[4] and others,[5] there are reasons to believe that it lacked the rich plasticism which characterizes these late-Republican portrait specimens. From what survives it appears in fact that the descriptive and dry realism of the head limited itself to the surface and did not penetrate beyond it in order to provide movement in facial muscles and to suggest the skull structure. Because of this it has several other parallels in Roman portraits sculptured in the round,[6] but most of all they abound in Roman funerary reliefs.[7]

By far the closest parallel for our head is an equally corroded head in the Museo Civico of Rimini, which seems to have once belonged to a relief.[8] It is almost an identical twin with the Valletta head, but in local limestone, not marble.

Date: On the basis of the above comparanda, this portrait probably belongs to the late Republic. Similarities with some portraits of nameless men dating to the early Flavian age on the basis of their likeness to imperial portraits, such as that of Vitellius and one of Vespasian, however, do not exclude a possible Flavian date.

Bibliography: (previous publications of item):

Ashby: 78, no. 16, fig. 34: “Head, almost bald, of old man with grumpy expression, 10 ins. high; nose almost gone. Perhaps of the republican age. Provenance unknown: museum no. 67.” Zammit 1919: 25: “old man with austere expression, 10 ins. high, badly battered, and nose nearly gone”. Bonanno 1971: 113-116.

[1] Zadoks and Jitta 1932; Schweitzer 1948: 19-33; Rollin 1979: 5-37; Lahusen 1985: 308- 323.

[2] Richter 1955: 39-46; R. Bianchi Bandinelli, s.v. Ritratto, EAA VI (1965): 718-25; K. Fittschen, s.v. Ritratto, EAA, IIo Suppl. IV: 752-3, bibliography on pp. 758-60.

[3] Calza 1964: 26-7, nos. 22-4, pls. 14-15.

[4] Richter 1941: nos. 1-5.

[5] García y Bellido 1949: 52-3, no. 40 (‘Flavian or Trajanic’); Adriani 1970: pls. 32-3.

[6] Comstock & Vermeule 1976: 201, no. 320; Kaschnitz-Weinberg 1936-37: 257-8, nos. 592, 596 (almost identical: ‘inizi età augustea’), pl. 95); Adriani 1970, pls. 36-7.

[7] Vessberg 1941: 173-208, pls. 26-45; Calza 1964: 25-6, nos. 19, 21, pls. 12-13; Comstock & Vermeule 1976: 200-1, no. 319; Giuliano 1957: nos. 1-3, pls1-2.

[8] Mansuelli and Vergnani 1964: pl. 13, 35; 1965: 129, no. 197.